This book, Colloquial Kansai Japanese, by DC Palter and Kaoru Slotsve, is great, and I see it recommended online a lot as a good resource, but please bear in mind, this book was published in 1995, and doesn’t seem to have been updated since then. As a result, a lot of the examples given in it are outdated, and no longer used.

I asked an Osaka native about some of the ones I was suspect about, and this is what she said (translated from Japanese):

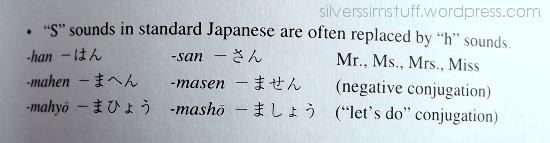

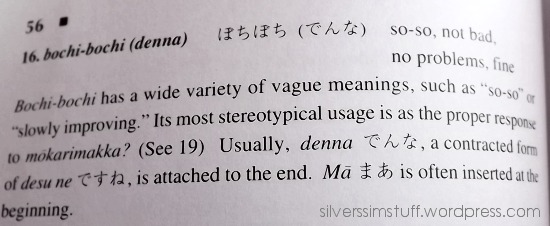

It would be great if young people used “dekka” and “denna”. Sometimes we use it for making fun. It’s the same for saying “dekimahen” [instead of dekimasen] and “ikimahyo” [instead of ikimashou], and “Tanaka-han” [instead of Tanaka-san]! Old people use it. I think the words listed in that old text will stop being used.

So there you have it. It’s still a good book, but unless you want to sound like someone speaking esekansaiben — the Kansai equivalent of bad Mockney — it’s best to check the info given with a native speaker first.

One thing that’s interesting, is that the old Kansai-ben actually has many parallels with Surati Gujarati. We soften many S sounds to H sounds. For example, standard “sun che?” (what is it?) becomes “hun che?” and “sabun” (soap) becomes “habun”. It also has a reputation of sounding rougher than standard.

Surati Gujarati: This is spoken in the southern part of the state of Gujarat. It can sound a bit harsh and is known to have many bad words in it. This region is known for their fondness for luxury and food.

From: Gujarati Language: 5 Different Accents in Gujarat

One thing I have to say: old lady Gujarati is hilarious. There’s no contest between saying the same thing in English vs Old Lady Gujji. Old Lady Gujji is always better.

One big difference is that I can easily still recognise Kansai-ben speakers as speaking Japanese, even if I barely understand a word, whereas I can’t even recognise standard Gujarati as the same language. I study Portuguese on and off, and it’s enough for me to be able to understand some Spanish and even have conversations with a colleague, where she’d speak Spanish and I’d speak Portuguese, but I can’t even tell that someone is speaking standard Gujarati. Yuki-sensei then pointed out that the difference between my dialect and standard must be even bigger than the difference between Spanish and Portuguese. And it’s true.

I have one of those crappy “Learn Gujarati in Three Months” books, and I swear I’ve never heard of most of those words. A few are the same as what I know, a few are slight variations (like sabun/habun (which came from Portuguese sabão, who knew?)). But for the majority of words, there’s no recognition. Now I need to point out that my knowledge of my mother-tongue is latent. I can barely speak it, but I can understand my family’s dialect fluently. It’s strange how two distinct languages, like Spanish and Portuguese, can be more mutually intelligible to me than two dialects of the my own language.